|

| Frankie Sardo |

Frankie Sardo was born Frank Marco Sardo in Italy in 1936, although most sources incorrectly claim he was born in 1939. His exact date of birth is unknown (at least to me). His father, Marco, worked in show business. Frankie was only five years old when dad got him up on stage, acting, dancing and singing. The family came to America to escape World War II and settled in New York City where Frankie attended grade school. When he left high school, somewhere around 1952, Frankie went into the United States Army for a couple of years, serving through the end of the Korean War in 1953. When he returned around 1954, he went to Virginia to continue his education. He kept busy in the theater while attending school, both acting and singing in various plays, some of which he even produced himself. When he got back to New York City in 1958, he went into the recording studio with his brother and cut his first of eleven singles. Here’s the complete discography:

1958 – MGM 12621 – My Story Of Love / May I

1958 – MGM 12678 – Let’s Go Rock / Midnight Stomp

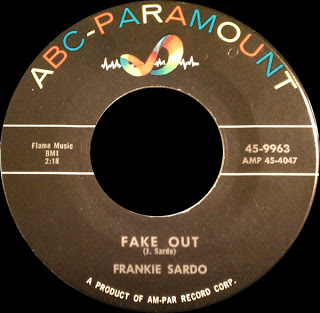

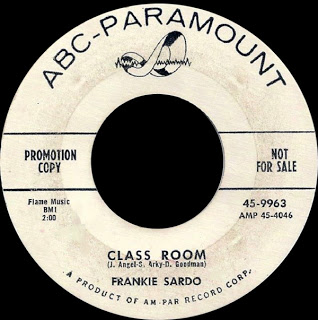

1958 – ABC/Paramount 9963 – Class Room / Fake Out

1959 – ABC Paramount 10003 – Oh Linda / No Love Like Mine

1959 – Lido 602 – Kiss And Make Up / The Girl I’m Gonna Dream About

1959 – Lido 604 (as Frankie And Johnny) – Big Clem / Together Tonight

1960 – 20th Fox 208 – When The Bells Stop Ringing / I Know Why And So Do You

1960 – 20th Fox 221 – Dream Lover / Bonnie Bonnie

1960 – SG 1 – She Taught Me How To Cry / Ring Of Love

1961 – Studio 9910 – I’m Sittin’ At Home / Just You Watch Me

1962 – Newtown 5005 – I Got You Where I Want You / Mister Make Believe

1962 – Rayna 5005 – She Taught Me How To Cry / Ring Of Love (reissue or remake of above SG 1 from 1960)

Out of all these records, and most of them are more than good enough to have become big hits, only one made the national charts. That one was today’s New Oldie, Fake Out, written by Frankie’s brother John, which made its debut in Cashbox magazine on 6 December 1958 where it lasted six weeks and peaked at #68. It was never listed in Billboard’s Hot 100. The single was favorably reviewed, however, in Billboard’s 6 October 1958 issue as a Pick of the New Releases.

Frankie had invited a friend from Brooklyn named Victor Bonadonna, who sang under the name Vic Donna, to the session where he recorded Fake Out and Class Room. Frankie wasn’t satisfied with the sound they were getting out of Fake Out and the Producer felt there was something missing. Vic said, “I have an idea. I think on certain parts there should be a little harmony.” The invited Vic into the studio where he grabbed a mike and sang the backing vocals. Everyone loved it! Frankie’s manager invited Vic to join forces with him and Vic agreed.

Here’s Fake Out by Frankie Sardo on ABC/Paramount 9963 from 1958:

|

| Promo Copy Label |

And here’s the flip side, Class Room:

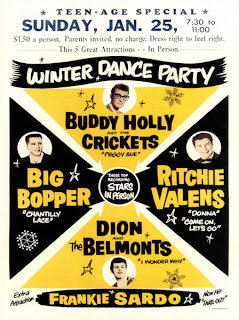

While Fake Out was climbing the Cashbox charts, mainly due to airplay and record sales in the Midwest, Frankie was invited to be the opening act for the 1959 Winter Dance Party tour alongside rock and roll legends Buddy Holly and the Crickets, Ritchie Valens, The Big Bopper (J. P. Richardson), and Dion And The Belmonts. Frankie’s name appears on the bill as an “Extra Attraction” (above), but you’ll notice that his “New Hit” is incorrectly listed as “Take Out.” Oops!

|

| Buddy Holly Crash Site – Clear Lake, Iowa |

Frankie shared a room with Ritchie Valens while staying in Clear Lake, Iowa, to perform in the show on 2 February 1959. Backing musicians included Tommy Alsop on guitar, Waylon Jennings on bass, and Carl Bunch on drums, who were billed as The Crickets. This would end up being the final show for Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and The Big Bopper. Later that night, Buddy chartered a small plane to take him to Moorhead, Minnesota from the nearest airport in Mason City, Iowa. It was snowing like crazy. The pilot, Roger Peterson, finally took off shortly after midnight, despite the fact that the flight would heavily rely on instruments and Roger was only qualified to fly in clear weather. There was only room for three passengers. Waylon Jennings won a seat on the flight, but gave it up to Buddy Holly and rode the bus instead. Buddy yelled to him, “I hope your ol’ bus freezes up!” Waylon replied, “Well, I hope your ol’ plane crashes!” It was a statement that would haunt Waylon Jennings for many years. The plane crashed shortly after takeoff near a fence that was built to separate two cornfields. The four bodies laid in the blowing and drifting snow all night. This is the night Don McLean is talking about in American Pie when he sings, “February made us shiver, with every paper I delivered, bad news on the doorstep, I couldn’t take one more step.” Ritchie Valens was only 17 years old and left his new bride that night. Buddy Holly’s new bride, Maria Elena Holly, was just two weeks pregnant that night. She learned about her husband’s death through news reports. This was very painful, of course, and it’s the reason why the names of people killed are now withheld from the press until after the family has been notified. Her pregnancy would later end in a miscarriage, putting an end to the Holly family tree. She’s blamed herself for the tragedy. Normally, she tagged along with her husband when he went on tour. But she stayed home that night because she wasn’t feeling well. Had she gone with him, she believes, he would not have been on that airplane. She did not attend the funeral, and she has never visited his grave in Lubbock, Texas. That’s what Don McLean talks about in American Pie when he sings, “I can’t remember if I cried, when I read about the widowed bride. Something touched me deep inside, the day the music died.”

Frankie continued recording through 1962, never breaking through with a national hit song. That’s when he got married and tried his hand at record producing, off-Broadway theater, and even working night clubs with his father, Marco. Frankie headed to California in 1968. His first project was to help produce music for the movie Hell’s Angels ’69.

On 12 November 1971, while visiting London, Frankie, along with six other men, were arrested after Scotland Yard detectives raided a luxury apartment in the Mayfair district. The group was charged with conspiracy to commit what was first described as the theft of a million dollars worth of stock certificate blanks printed for Westinghouse Electric and Continental National Bank and Trust of Chicago. In reality, the 5,000 blank stock certificates were printed at the American Bank Note Company in New York. On 4 October 1968, they were delivered to Emery Air Freight for shipment via American Airlines to Chicago. When the plane carrying the notes arrived at O’Hare airport, the certificates were missing. The actual FBI complaint in Los Angeles listed the blank securities as $30 million and claimed they had been intended for delivery to four American companies when they were stolen in August 1971. The seven men arrested included:

35 year old movie producer Frank Sardo of Los Angeles, California;

Movie producer Rudolph Johnson of Cannes, France;

52 year old Charles Samuel Bufalini of Los Angeles, California;

39 year old record producer James Walker of Los Angeles, California;

29 year old Terry (???nzi) of Highland Park, Illinois;

50 year old financier Marion Arthur Denark of London, England;

Record producer Nicholas Avenelli of Los Angeles, California.

The FBI had the California men under surveillance when they boarded a plane from Los Angeles to London. Scotland Yard was notified and the English detectives continued watching the men as they left the airplane together, took their luggage, and watched them arrive at the apartment together. All were held in Brixton Jail in South London awaiting trial in London or possible extradition to Chicago. Rudolph Johnson tried to claim that he didn’t know any of the other men, but had once made a movie with Frankie Sardo. When he heard Frankie would be coming to London, he asked him to bring along some cigarettes. He told authorities that he was only visiting the apartment to pick up those cigarettes at the time of the raid. By themselves, phony stock certificates have no value because they would be inspected and identified as forgeries if anyone ever tried to cash them in. However, they could be used as collateral for a loan. Most fraud cases like this are discovered when someone takes out such a loan and then disappears. Frankie was eventually acquitted of all charges. It appears that another man, Anthony Ditata, was ultimately arrested, indicted, and convicted of using the notes as collateral for fraudulent loans. In 1972, Ditata tried to appeal on the grounds that the value of the notes were less than $100, making the crime a misdemeanor. Despite this claim, the conviction was upheld.

After that bizarre experience, Frankie returned to Hollywood to make movies and changed his last name to Avianca, which was his mother’s maiden name. Here’s a list of some of his projects:

1971 – Executive Producer – Clay Pigeon

1973 – Producer – The 14 (also distributed under the names Existence and The Wild Little Bunch)

1975 – Producer and Actor – The ‘Human’ Factor

1978 – Actor – Matilda

1982 – Producer – Blood Song (also distributed as Dream Slayer)

1988 – Producer – The Undertaker

1999 – Producer – The Survival Club

2000 – Producer – Blame It on the Moon

An annual show and symposium is held each year around February 2nd, the anniversary of the Winter Dance Party tragedy. Frankie was invited to attend this show several times, but he always refused.

On the 50th anniversary, in 2009, Frankie finally agreed to make an appearance. He signed autographs on Saturday afternoon, then spoke on a panel on Saturday evening in the E.B. Stillman Auditorium at Clear Lake Middle School called “The Last Tour” where Frankie Avianca (Sardo), Tommy Allsup, Carl Bunch, Bob Hale, Carlo Mastrangelo, and Freddie Milano recalled good memories, horrible weather conditions, and shared stories about the last show. It was at this panel where the world learned why Frankie had been avoiding the Surf Ballroom for 50 years. He admitted that survivor guilt kept him away. He had always felt the anniversary gathering was commercializing the tragedy. After finally returning, Frankie’s feelings changed. “This showed me how wrong I was about how I conceived it to be. I thought it would be some commercial thing, one of those morbid sad things; milked. But it wasn’t that at all. It’s quite the opposite, really.” Instead of sorrow, what Frankie recalled during his return was the kids who came to see the show and their laughter and joy. Frankie continued, “I tell a lot of my friends, I was not in their league. I never wanted to be a rock and roll star. I didn’t want to be a singer.” He went on to say, “I was just a Korean War veteran who got caught up in it, was taking advantage of it and having fun. I was in between whatever life had in store for me.” According to Frankie, “I was just having fun and, luckily, I could carry a tune!” He also admitted that, although he’d been avoiding the Surf Ballroom, he had once paid a visit to the farm where the plane came down after a business trip to Chicago. During that visit, he left flowers there in memory of his friends.

By the way, my first visit to that site was a very moving experience. I went back there with four friends and we all felt the same thing. It’s like being surrounded by ghosts, but you aren’t scared. Instead, you’re overwhelmed with the feeling that you’re members of an audience and they’re really happy you came to see them.

A year later, the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, in conjunction with the Surf Ballroom and Museum presented a luncheon in Clear Lake where they featured The Frankie Sardo Story.

Last I heard, Frankie’s still working as an independent film producer in New York City, also spending some time at a second home in Canada.

You’ll hear EVERY ONE of Frankie Sardo’s songs on MusicMaster Oldies, along with hundreds of other talented young people with similar stories. Check it out! Tell your friends! While you’re visiting, please take a moment to send a note to the DJ (that’s me!).