How many songs make it to number one on Billboard’s Hot 100 each year? Have those numbers been getting higher or lower over the years? The answer might surprise you. The reason for this might surprise you even more.

The average number of records that make it to number one in a given year (1955 to 2011) is very close to 20. That means that, on average, a record sits at the number one spot for about two and a half weeks. But something changed radically around 1992. The number of unique songs that reached the number one spot suddenly dropped — dramatically — and stayed there. The average number of #1 hits each year between 1955 and 1992 was about 24. But the average number of annual #1 hits from 1993 to 2011 dropped to around 13 1/2. What happened?

The years that produced the most #1 hits (since 1955) were 1974 and 1975, each giving us 35 unique #1 tunes. We saw 33 #1 hits in 1988 and 1989, and 32 of them in 1965. From 1955 to 1992 the number of top hits per year ranged from a high of 35 to a low of 13 (in both 1955 and 1992).

From 1993 to 2011, however, the number of top hits per year only ranged from a high of eighteen (in both 2000 and 2007) to a low of just eight (in 2005).

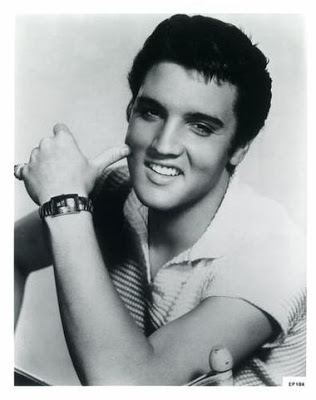

Clearly there are fewer number one hits on the chart in recent years. There are several factors that can explain minor variations. Every so often a huge hit comes along that simply sits at the top of the chart much longer than most other number one hits. For example, Elvis Presley’s huge 1956 hits, Don’t Be Cruel and Hound Dog, stayed in the number one spot for a whopping (for then) eleven weeks. They each stayed on the charts for just over half a year. When those huge songs hit the charts, they take up space at the top, blocking other songs from reaching the number one position. These monster hits account for much of the variation in number one songs from one year to the next. But that doesn’t account for what happened around 1992.

It used to be rare, but lately it’s become more common for a song to slip out of the number one spot, only to bounce back up to number one again a week or two later. It’s like a big song came along that pushed it’s way through to the top, but then dropped quickly, allowing a song with more longevity to jump back up again. There are clearly songs that have more staying power than others. Novelty records, for example, tend to have very poor staying power. Once you’ve heard the joke, it’s not funny the second time.

One possible explanation for the sudden decline in the number of unique number one hits each year since 1992 is that the music industry is producing songs with more longevity. Perhaps the industry has been paying attention to those longer lasting songs and figuring out what makes them hang around at the top of the charts. But does this suggest that Katy Perry and Lady GaGa are making better records than The Beatles or Elvis Presley? Maybe not better, but at least good enough to keep people from getting tired of hearing them quickly.

The Billboard charts are based on physical (and now digital) sales, with radio airplay factored in. There’s a synergy between the music business and radio. I heard this described brilliantly last week at the Country Radio Seminar in Nashville. One of Country music’s more prolific composers told the audience of radio programmers, “You can think of us as artists who paint beautiful pictures, but without you to hang them on the wall, nobody would ever see them.” Radio promotes music. Always has. Always will. Or will it? There’s been an ugly fight bubbling under the surface recently between radio and the music industry concerning performance royalties. The record companies used to let radio stations slide without paying these fees in consideration of the promotional value of exposing songs on the radio. That promotion used to sell records. It still does, of course, but to a lesser degree, especially among younger people.

Radio’s dirty little secret is that it’s not as effective at attracting the younger audience than it used to be. Young people today are exposed to new music from many different sources. Back in the 1950’s and 1960’s, you would only hear new songs when you listened to the radio, watched the occasional music variety show on television, or visited your local record store or a friend’s house. The Internet changed all that.

Today, iTunes is the easiest way to discover new music. You can see the top selling songs in the iTunes music store and sample them on your computer or phone. This leads you to other songs by the top artists, and also to music from other “similar” artists, some of whom are completely independent from any record company. The record companies are slowly becoming irrelevant when it comes to promoting new music, while the radio stations are slowly becoming irrelevant at exposing new music.

The distribution of digital music via the Internet and the use of personal MP3 players really started to pick up speed around 1992. It became much easier for listeners to enjoy their own playlists, even while on the go, so they didn’t spend as much time listening to the radio. There was also an explosion of illegal distribution of music, including new music, that had the potential to cut into record sales dramatically. Illegal music downloading could account for some of the variation in the Billboard charts, since they are based on legitimate record sales. The charts are also influenced by radio airplay, which really wasn’t affected by the Internet. Instead, the number of radio listeners and their demographics changed. This would have had an impact on the feedback that radio programmers received from their audience through research, and that could have affected airplay which, in turn, would have had an impact on the Billboard charts.

Radio programmers have been researching the music they play for many years, but their methods were not very scientific prior to the 1960’s. As the 1970’s passed by, radio research companies started to prefect the art of music preference measurement. It’s been getting even better ever since. Well, some say better, while others blame research for the smaller playlists and repetitive nature of radio today when compared with the “good old days.”

The fact is, radio stations are getting better at finding the better songs, dumping the weaker songs, which all means that hit records continue getting airplay for a much longer time than they did in the past. Radio programmers use different methods to measure the music preferences of their audience, but they’re all attempting to determine the same things. How many people (in our target audience) like this song? How many of them hate it? How many of them are tired of hearing it? How much does our audience think this song “fits” on our station? These factors act like a negative feedback that forces out the bad records quickly and keeps the good records playing much longer.

Almost all radio stations use computer software, such as MusicMaster, to create their playlists these days. In this software, the Program Director can assign each song to a Category, which controls the amount of time between repeat plays of that song. A big current hit will repeat much faster than a new release or an older song. Really old songs take much longer to repeat, or are removed from the system completely. The theory is that a radio station needs to consistently provide the musical product that their audience expects. It’s like how McDonalds hamburgers usually taste exactly the same no matter which store you visit anywhere in the country, or even the world. It’s not the best food, but you know what to expect when you visit McDonalds. The same thing happens with a well programmed radio station. You know what to expect whenever you tune in. If it’s a current hit radio station, you should hear a current hit every time you tune in, at least within one or two songs at the most. You should hear the current hits often because that’s what you expect. It’s how people “use” radio these days.

If music research keeps better records playing longer, it follows that the total sales for these songs should increase as well. Both of these factors push the top songs up the charts and keep them there longer. This is clearly the reason why there are fewer number one hits each year. The hits just last longer on the radio giving more people a chance to hear them, love them, and ultimately buy them.

It’s not necessarily a bad thing or a good thing. It is what it is. By the way, research shows that most people, as they get older, continue to prefer the music that was a current hit when they were fourteen years old. Take your birth year, add fourteen, and look up the top songs in that year. This should prove the point. There are exceptions, of course. But that statistic is pretty reliable. Researchers believe that our brains are actually imprinted with the music we heard during this particular time of our development from birth to adult.

I was fourteen in 1967, which probably explains why I’m so obsessed with the music of the 1960’s. If you’re younger than me (which, unfortunately, many people are these days), MusicMaster Oldies is probably not playing your favorite music. If you listen anyway, thank you. Think of it this way. When you listen to the oldies, you’re learning about the roots that eventually spawned and shaped the music you do prefer. I’ll be back with some more tunes in a bit. Thanks for letting me ramble on!